People aren’t supposed to survive metastatic colon cancer. Once the cancer progresses to this terminal stage, tumor cells from the colon spread rapidly throughout the body, with death the certain result. You have a better chance of winning the lottery than of surviving, once the cancer metastasizes.

Thus it was with considerable delight that cancer researchers at the meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in New Orleans learned last Monday of a patient who had done the seemingly impossible. Shannon Kellum, a 30 year old accountant from Fort Myers, Florida, learned in 1998 that she had terminal colon cancer, and could not expect to live long. The cancer had already spread to her liver, with tumors the size of grapefruits, far too large to remove. Her life expectancy was nil. Today she is tumor-free, and not at all dead.

How Shannon Kellum survived terminal colon cancer is an encouraging story to all of us who worry that we may someday face the same grim challenge. It is also a story which reveals a lot about how chance can play a key role in science’s ongoing efforts to subdue cancer.

Shannon’s cure owes a lot to Richard Nixon. The War on Cancer he initiated in 1972 has taught us a lot about cancer’s causes. There are many, but they all have this in common — cancer cells divide when they should not.

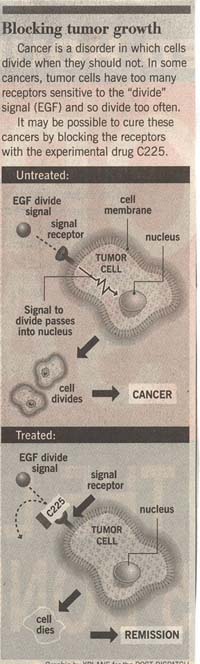

How do normal cells know when to divide? They wait to be told. Only when a proper “divide” signal is received do they divide. By 1979 scientists had isolated this “divide” signal, a small protein called epidermal growth factor, or EGF. Every cell has on its surface a few special antenna for detecting EGF. Called EGF receptors, these antenna have a shape that precisely matches that of EGF. Normal cell division is initiated when an EGF molecule snuggles into one of the antenna. Like ringing a doorbell, this initiates a series of events within that cause the cell to divide.

In many cancers, cells have become oversensitive to the “divide” signal EGF. Instead of waiting for a good, loud ringing of the doorbell, these cells start dividing madly at the faintest whisper of a tinkle. Why are they so sensitive? It turns out that two-thirds of all cancers have an excess of EGF receptors. Why does this make the cells more sensitive to “divide” signals? Imagine you were throwing a ping pong ball at a collection of targets on a wall — increasing the number of targets makes it more likely you will hit one. In just the same way, cells with excessive numbers of EGF receptors have a hair trigger, and divide when only a smidgen of EGF is around (and there is always a smidgen around).

This suggests a possible therapy: Maybe by gumming up the EGF receptors on cancer cells, we can prevent these cell from receiving the divide signal. The necessary tool can be made using the marvels of the new biology — a so-called monoclonal antibody. These antibodies seek out and bind like glue to a specific kind of protein, in this case EGF receptors, ignoring all others.

One of several monoclonal antibodies now being tested against cancer is the drug C225, which is showing good results in ongoing trials against head and neck cancer. C225 has been investigated for over a decade by John Mendelsohn, president of the M.D.Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Working under Mendelsohn as a research fellow in 1991-92, a budding doctor named Mark Rubin looked into the effects of C225 on other cancers. He focused his attention on colon cancer cells, which seemed very sensitive to C225. Interestingly, the cells not only stopped growing when they were prevented from receiving EGF — they actually committed suicide!

Now here is where the story intersects Shannon Kellum’s dilemma. Seven years later, Rubin had completed his training and was a practicing oncologist (cancer specialist). Into his office appears Kellum with advanced colon cancer. Chance certainly favored her that day, picking that particular doctor. After chemotherapy failed, with little prospect of any outcome but death, Rubin remembered his work years ago with C225 and got on the phone to Mendelsohn. With special permission from the FDA, Kellum was administered C225 in April of 1999.

The drug was administered to Kellum once a week intravenously, with chemotherapy to aid in knocking out any tumor cells weakened but not killed by lack of EGF. Her liver tumors shrank by 80% in four months. Four months later, the tumors were small enough to be removed surgically. Today she is tumor-free. Only time will tell if she is cured — some cancer cells may remain that could restart tumors. But there is no denying the fact that she is very much alive and leading a normal life, a year after she should have died.

Cancer has many causes, and no one discovery is going to cure it. While research on many battlefronts is whittling away at the problem, the job is a big one, and the war against cancer is far from won. Its nice to win a skirmish once in a while, though.

© Txtwriter Inc.