African bees have invaded the south, and may eventually reach Missouri

One of the harshest lessons of environmental biology is that the unexpected does happen. Precisely because science operates at the edge of what we know, nosing ahead to learn more, researchers sometimes stumble over the unexpected. This lesson was brought clearly to mind this summer, with reports of killer bees being discovered for the first time east of the Mississippi River, in Jacksonville, Florida.

In Missouri we are used to the mild mannered European honeybee, a subspecies called mellifera. The African variety, subspecies scutelar, look very much like them, but they are hardly mild mannered. They are very aggressive, with a chip on their shoulder, and when swarming do not have to be provoked to start trouble. A few individuals may see you at a distance, loose it, and lead thousands of bees in a concerted attempt to do you in. The only thing you can do is run — fast. They will keep after you for up to a mile. It doesn’t do any good to duck under water, as they just wait for you.

They are nicknamed “killer” bees not because any one sting is worse than the European kind, but rather because so many of the bees try to sting you. An average human can survive no more than 300 bee stings. A horrible total of more than 8,000 bee stings is not unusual for a killer bee attack. An American graduate student attacked and killed in Costa Rican jungle had 10,000 stings.

The reason killer bees remind me of the “law of unintended consequences” is that their invasion of this continent is the direct result of researchers stumbling over the unexpected.

Killer bees were brought from Africa to Brazil 43 years ago by a prominent Brazilian scientist, Warwick Estevam Kerr. A famous geneticist, Kerr is the only Brazilian to be a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. What he was doing in 1956, at the request of the Brazilian government, was attempting to establish tropical bees in Brazil to expand the commercial bee industry (bees pollinate crops and make commercial honey in the process). African bees seemed ideal, better adapted to the tropics than European bees and more prolific honey producers.

Kerr established a quarantined colony of African bees at a remote field station outside the city of Rio Claro, several hundred miles from his university at San Palo. While he had brought back many queens from South Africa, the colony came to be dominated by the offspring of a single very productive queen from Tanzania. Kerr noted at the time that she appeared unusually aggressive.

In the fall of 1957 the field station was visited by a bee keeper. As no one else was around that day, the visitor performed the routine courtesy of tending to the hives. A hive with a queen in it has a set of bars across the door so the queen can’t get out. Called a “queen excluder,” the bars are far enough apart that the smaller worker males can squeeze through. Now once a queen starts to lay eggs, she’ll never leave the hive, so there is little point in slowing down entry of worker males to the hive and the queen excluder is routinely removed. On that day, the visitor saw the Tanzanian queen laying eggs in the African colony hive, and so removed the queen excluder.

One and a half days later, when a staff member inspected the African colony, the Tanzanian queen and 26 of her daughter queens had decamped. Out into the neighboring forest they went. And that’s what I meant by being bushwhacked by the unexpected. European queen bees never leave the hive after they have started to lay eggs. No one could have guessed that the Tanzanian queen would behave differently. But she did.

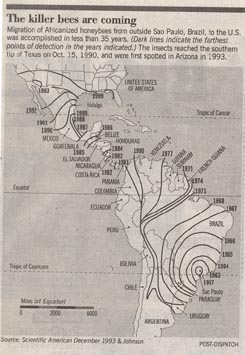

By 1970 the super-aggressive African bees had blanketed Brazil, totally replacing local colonies. They reached Central America by 1980, Mexico by 1986, and Texas by 1990, having conquered 5 million square miles in 33 years. In the process they killed an estimated 1,000 people and over 100,000 cows. The first American to be killed, a rancher named Lino Lopez, died of multiple stings in Texas in 1993.

All during the 1990s the bees have been invading the United States. All of Arizona and much of Texas has been occupied. Last spring all of Los Angeles County was declared officially colonized, and it looks like African bees will eventually move at least half way up the state of California.

In a few years the invasion is predicted to cease, on a line roughly from San Francisco to Richmond. Winter cold is expected to limit any further northward expansion of the invading hoards.

That line includes Missouri, barely. So, sure as the sun rises, the killer bees are coming, not caring one bit that they were unanticipated. The deep lesson — that unexpected things do happen — is being driven home by millions of tiny aggressive teachers.

©Txtwriter Inc.