One evening next week I am to audition for a part in Saint Louis Shakespeare’s upcoming production of WAR OF THE WORLDS (Don’t ask me why a Shakespeare company is putting on a play based on a radio drama by H. G. Wells!), in which invaders from Mars attack Earth. With this sort of prospect buzzing in the back of my mind, I cannot help but note a lot of stories about Mars in the news lately. Last week I learned that the trusty little rovers NASA has had sniffing around on the Martian surface this last spring has found jet-fuel-like chemicals in the Martian soil that would be pretty hard to live with. On the other hand, reports in the weeks before strongly support the idea that there used to be oceans on Mars, and even suggest that there may be liquid water there now just the sort of place life might evolve.

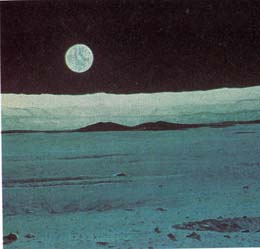

This isn’t the first time we have been teased with the possibility of life elsewhere within our solar system. In the nineteenth century it was commonly speculated that life might exist on the moon. In 1865 the French novelist Jules Verne described moon men in From Earth to the Moon. We now know that life never evolved there. Life did, however, reach the moon in 1969. The planet from which it came can be seen in the photograph above, rising above the distant hills in the moon’s twilight.

Ever since the erroneous reports of canals on Mars by nineteenth century astronomers, it has been speculated that life in some form might exist there. In the mid-1970s the first of many space probes landed on the martian surface to explore for life. Extensive tests were done on soil samples, but no evidence of life was found. Nor has any direct evidence of life been found by the two rovers now scurrying over the martian landscape. Like the teasing suggestion of watery seas, all we have are insubstantial hints.

Here’s another one. A dull gray chunk of rock collected in 1984 in Antarctica ignited an uproar about ancient life on Mars with the report that the rock contains evidence of possible life. Analysis of gases trapped within small pockets of the rock indicate it is a meteorite from Mars. It is, in fact, the oldest rock known to sciencefully 4.5 billion years old. Back then, when this rock formed on Mars, that cold, arid planet was much warmer, flowed with water, and had a carbon dioxide atmosphereconditions not too different from those that spawned life on earth.

When examined with powerful electron microscopes, patches within the meteorite exhibit what at first glance look like bacteria. While this initially created quite a stir, the tiny microfossils proved to be only 20 to 100 nanometers in length, one hundred times smaller than any known bacteria, and scientists now believe them to be carbonate aggregations resulting from everyday chemical processes, rather than the carcasses of ancient bacteria. However, while there now appears to be no real evidence of bacterial life associated with this meteorite, this absence in no way rules out the possibility that life has evolved on Mars there’s just none of it evident in this particular bit of it.

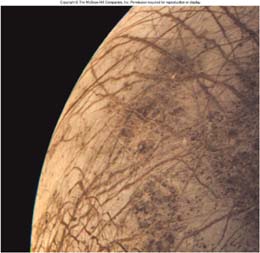

Nor is Mars the only place in our solar system with conditions that might foster the evolution of life. Europa, a large moon of Jupiter, is a promising candidate. Europa is covered with ice, and photos taken in close orbit in the winter of 1998, like the one shown here, reveal seas of liquid water beneath a thin skin of ice. Additional satellite photos taken in 1999 suggest that a few miles under the ice lies a liquid ocean of water larger than earth’s, warmed by the push and pull of the gravitational attraction of Jupiter’s many large satellite moons. The conditions on Europa now are far less hostile to life than the conditions that existed in the oceans of the primitive earth. In coming decades, satellite missions are scheduled to explore this ocean for life.

In the meantime, while we await the results of future Europa probes, what are we to believe? Does life exist on other worlds? Looking up at the sky on a starry night, it is difficult not to wonder if there might be life somewhere up there., outside our solar system. Because our exploration of space is limited, we can only speculate or at the very most, make educated guesses, at what lies out there, far off in space. The nearest galaxy to ours is a spiral galaxy called Andromeda. It contains millions of stars, many of them resembling our own sun. While planets have not yet been discovered orbiting the stars of Andromeda, it seems certain that thousands exist.

The universe contains over a billion galaxies, with 1020 (100,000,000,000,000,000,000) stars similar to our sun. We don’t know how many of these stars have planets, but it seems increasingly likely that many do. Since 1996, astronomers have been detecting planets orbiting distant stars. At least 10% of stars are thought to have planetary systems.

Is it likely that any of these far planets harbor life? What would the distant planets have to be like? The life forms that evolved on earth closely reflect the nature of this planet (water rich) and its history (oxygen gas becoming common in the atmosphere only later). If the earth were farther from the sun, it would be colder and chemical processes would be much slower. Water, for example, would be a solid, and many carbon compounds would be brittle. If instead the earth were closer to the sun, it would be warmer, chemical bonds would be less stable, water would be a gas, and few carbon compounds (carbon is the basis of all life here on Earth) would be stable enough to persist. The evolution of a carbon-based life form is probably possible only within the narrow range of temperatures that exist on earth, which is directly related to its distance from the star it orbits, the sun.

The size of the earth has also played an important role in favoring life, because it has permitted a gaseous atmosphere. If the earth were smaller, it would not have a sufficient gravitational pull to hold an atmosphere, and it would be cold and lifeless. If it were larger, it might hold such a dense atmosphere that all solar radiation would be absorbed before it reached the perpetually cold surface of the earth.

How many far planets are roughly the same size as earth, and the same distance from their sun? We don’t as yet have any way to estimate, although every year we learn more about planets that orbit distant stars. All we can do now is guess. If only 1 in 10,000 of these planets is the right size and at the right distance from its star to duplicate the conditions in which life originated on earth, the “life experiment” will have been repeated 1015 times (that is, a million billion times).

If so many planets in the universe may harbor life, why haven’t we heard from anyone? Radio and television signals can easily travel between the stars. Indeed, every radio and television program ever broadcast on earth will eventually reach the stars, although as a very weak signal. Elvis Presley’s appearance on the Ed Sullivan show in 1957 reached the nearest star Zeta Herculis after travelling 31 light years. If they were to respond, we might expect to hear from them in ten years.

We will be listening. The Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project, initiated in 1992 and popularized in the film CONTACT, is designed to listen to radio frequencies deemed likely for alien messages. Using new multi-channel spectrum analysis techniques, the project simultaneously monitors millions of channels over the entire range of clear radio frequencies that reach the earth from space..

It does not seem likely to me that we are alone. Our own galaxy, a small spiral galaxy called the Milky Way, contains millions of stars. Looking up on a clear night, I find it impossible not to ask myself, “On planets orbiting how many of these stars is someone studying the stars and speculating on my existence?”

It would seem I am just the sort of person to cast in WAR OF THE WORLDS.

© Txtwriter Inc.