Eyeball-to-eyeball with mad cow disease Why mad cow disease is spreading across Europe and what we can do to stop it coming here

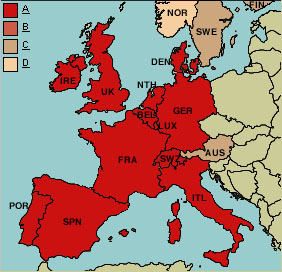

The countries of Europe are at war with mad cow disease. This week the German government ordered the destruction of 400,000 cattle in a draconian attempt to halt the outbreak there. Last week a program to destroy 25,000 cattle per week began in Ireland. The Irish expect to destroy 300,000 by June. Infected cows have also been reported this winter in herds in France, Denmark, Poland, Spain, and Italy. Entire herds are slaughtered when one member is found to be infected with mad cow disease. Overall, the European Union plans to eliminate 2 million potentially infected cattle by summer, at an estimated cost this year of $1 billion.

Why does the spectre of mad cow disease still loom over Europe? It has been over 15 years since the outbreak of mad cow disease in Britain led to the slaughter of fully a third of all the cows in Britain, 3.7 million animals. While warnings of the danger posed by infected cows came too late for British consumers, the other countries of Europe had not felt themselves at risk, because all of these countries had banned the import of British beef. In the late 1990s, as British citizens began to die of the disease, the rest of Europe watched horrified, glad to have dodged the bullet. Only now we see they hadn’t.

What happened? How did mad cow disease spread to Germany and the other countries of Europe? Can it find its way to our shores too? Are the 100 million cattle of our country at risk? Are we?

These are important questions, worthy of serious attention. Many reports are appearing in the American press, some alarming, others dismissing the danger here as remote. To sort through the confusion, it is necessary to clearly understand the nature of the disease, and how it is transmitted. To help, here is a primer on mad cow disease, and my assessment of what we should be doing in America to lessen the danger of an outbreak here.

What causes mad cow disease?

“Mad cow disease” is a fatal and communicable brain disease of cows that has a very long incubation period. Decades after infection, the brains of infected cattle develop numerous small cavities as nerve cells die. The holes produce a marked spongy appearance that gives the disease its scientific name, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Central nervous system function is progressively degraded, until death eventually occurs. There is no cure.

Mad cow disease is remarkable in that it is not transmitted by a virus or other microbe. Instead, a protein molecule spreads it from one individual to another!

Proteins are made as long strings, like spaghetti, each then folding itself up into a compact shape. The shape it assumes determines how the protein functions in an organism.

BSE is thought to have started when a key brain protein called a prion made a mistake and folded itself up incorrectly. Tragically, this protein, when it encounters others of the same sort, is able to induce them to refold into this same mistaken shape. A wave of misfolding relentlessly expands through the brain like a chain reaction. And, like a spreading rumor, any brain receiving a copy of the misfolded protein experiences the process anew.

Outbreak of mad cow disease in Britain

Therein lies the problem. Prions from the brain of an infected cow can cause the disease in other cows. Because cows normally eat grass rather than each other, you would not expect prion infection to be a problem for cows. However, until recent years it was the practice in Britain to supplement cattle feed with extra protein, and guess where the added protein came from! Often, from the “rendered” bodies of cows that had died in the field. It would be difficult to invent a more perfect way to spread the BSE disease.

Something was bound to happen, and in the mid-1980s it did. There was a major outbreak of mad cow disease in Britain, with many thousands of cattle affected each year for more than a decade. Some 750,000 infected British cows entered the human food chain as hamburgers, sausages and other meat products before the infected herds were slaughtered and the outbreak among cattle brought to an end.

But the warnings came too late for British consumers. In late 1995 the first human cases of mad cow disease appeared. Two teenagers were diagnosed with a rare disorder, typically of the elderly, called Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD). CJD has an array of symptoms and brain lesions similar to BSE. The sick teens did not live long. Analysis of their brain tissue revealed dense deposits of prion proteins called “plaques,” similar to those seen in BSE-infected cows but very different from what is usually seen in CJD. Researchers concluded that they had died of BSE — the mad cow disease agent had passed from cows to humans! Doctors refer to this human version of mad cow disease as “variant CJD” (vCJD).

In the five years since then, cases of vCJD have continued to surface. Sadly, the British government’s CJD surveillance unit reports that the incidence of vCJD is rising sharply. 14 Britons dies of vCJD in 1999, and 21 Britons last year.

This is very sad news, as it tells us the British are probably in the early stage of an epidemic. While only 90 fatal cases have been reported so far, many more vCJD cases are expected to appear as the prions from all that BSE-infected beef work their way through the British population. Researchers can only guess how many people have been infected. Mathematical models predict 136,000. Other researchers suggest that about 10,000 cases would be a more realistic estimate. Either number is a tragedy.

What should we do to lessen the danger ?

Mad cow disease and AIDS haunt the beginning of the 21st Century. The twin terrors of these epidemics are lethality (both are 100% fatal) and invisibility (both reveal no signs of disease until many years after infection). On balance, we have done well in fighting AIDS. Three of the lessons we have learned combating AIDS will serve us well as we now turn to face mad cow disease.

1. Devise a test for the disease agent. Early in the AIDS epidemic, investigators — led by Gallo of the NIH — developed tests for the presence of the AIDS-causing HIV virus. More than any other thing, the mad cow epidemic cries out for that sort of test. Without it, the only sure way to detect the presence of the disease is to sample brain tissue from dead animals. Animals that appear healthy cannot be tested to see if they harbor the disease-causing prion.

A few researchers like Gallo are reportedly at work trying to devise such a test. Our country cannot afford to sit around waiting. The federal government should immediately make the development of such a test a national research priority. Focusing many excellent minds on this key goal will increase the probability of a quick solution.

2. Focus on prevention. In the meantime, while there is no need to panic, we should heed the warning ignored by our mad-cow-infected European friends. How did BSE spread to the cattle herds of Europe? Europeans fixated on the infected British cows, and ignored the disease agent. The disease initially spread in Britain because cows were fed protein-supplemented feed — meat and bone meal (MBM) prepared from animals infected with BSE. But although there is a thriving international trade in MBM, nothing was done by Europe to restrict their exposure to meal prepared from BSE animals. The European Union has only this month imposed a six-month ban on MBM, extending its more limited ban on protein supplements.

3. Don’t wait to lock the barn door until after the horse is gone. It is important that regulations focus carefully on preventing transmission of the disease agent. The prion proteins that cause BSE are present primarily in nervous tissue. Because the skull and spine that make up a large portion of bone meal are easily contaminated with brain and spinal tissue during “rendering,” bone meal prepared from cattle is a real source of danger.

The focus here has been on preventing the use of protein feed supplements prepared from cows. It wasn’t until last month that the United States banned the import of cow bone meal. We still allow the importing of bone meal prepared from pigs and other animals raised on feed supplemented with cow MBM. We should stop this practice at once, as it is quite possible (even likely) that BSE prions can pass from cow to pig and back.

We are lucky to have escaped, so far, the devastating outbreak of mad cow disease that imported MBM has brought to European countries. The Texas cattle herd that was found to have been fed banned bone meal, quarantined last week, has proved to be clear of any BSE.

The importance of compliance

The lesson we need to learn is that no magic barrier keeps the disease out of The United States. What keeps it out is a stout barrier of regulation — rules and inspections designed to protect our cattle industry from infection by imported feed or animals bearing the disease. It is a well-thought-out barrier, and I have little doubt it can be effective.

However, a rule is only as effective as its enforcement. Disturbingly, recent checks have shown the barrier of regulations meant to protect us are often ignored. The Food and Drug Administration reported last month that a quarter of the 180 large American companies involved in manufacturing animal feed are not complying with regulations meant to prevent the spread of mad cow disease in this country.

This lack of compliance is scary. Marianne Elvander of the Swedish National Veterinary Institute is quoted by Reuters as saying “Negligent compliance with the meat and bone meal ban is the main reason for the spread of BSE in Europe.” FDA veterinary chief Dr. Stephen Sundlof issued a statement two weeks ago agreeing: Europe’s mad cow crisis “is not a result of them not having adequate regulations in place — it was a problem of enforcement.”

These FDA regulations are our only firewall against American mad cow disease. The FDA has warned that continued violations will prompt company shutdowns and prosecutions. Exactly right. I’d sleep better if the FDA immediately announced a plan to dramatically increase its surveillance of compliance with those regulations. They need more inspectors, if a quarter of the feed companies are not following the rules.

Should we stop eating meat, like many are doing in Europe? Not me. There is no evidence of a problem here now, only a nagging worry. If our government does its regulatory job, then I will be able to eat the steaks I love with no worry, and hamburgers too.