2. Natural selection can produce evolutionary change.

A variety of different processes can result in evolutionary change. Nonetheless, in agreement with Darwin, most evolutionary biologists would agree that natural selection is the process responsible for most of the major evolutionary changes that have occurred through time. Although we cannot travel back through time, a variety of modern-day evidence confirms the power of natural selection as an agent of evolutionary change. These data come from both the field and the laboratory and from natural and human-altered situations.

The Beaks of Darwin’s Finches

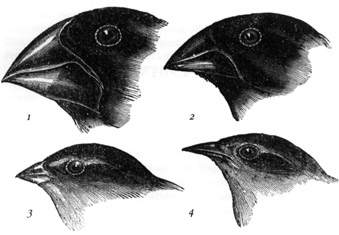

Darwin’s finches are a classic example of evolution by natural selection. Darwin collected 31 specimens of finch from three islands when he visited the Galápagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador in 1835. Darwin, not an expert on birds, had trouble identifying the specimens, believing by examining their bills that his collection contained wrens, “gross-beaks,” and blackbirds. You can see Darwin’s sketches of four of these birds in figure 8.

The Importance of the Beak

Upon Darwin’s return to England, ornithologist John Gould examined the finches. Gould recognized that Darwin’s collection was in fact a closely related group of distinct species, all similar to one another except for their bills. In all, there were 13 species. The two ground finches with the larger bills in figure 8 feed on seeds that they crush in their beaks, whereas the two with narrower bills eat insects. One species is a fruit eater, another a cactus eater, yet another a “vampire” that creeps up on seabirds and uses its sharp beak to drink their blood. Perhaps most remarkable are the tool users, woodpecker finches that pick up a twig, cactus thorn, or leaf stalk, trim it into shape with their bills, and then poke it into dead branches to pry out grubs.

The correspondence between the beaks of the 13 finch species and their food source immediately suggested to Darwin that evolution had shaped them:

“Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species has been taken and modified for different ends.”

Was Darwin Wrong?

If Darwin’s suggestion that the beak of an ancestral finch had been “modified for different ends” is correct, then it ought to be possible to see the different species of finches acting out their evolutionary roles, each using their bills to acquire their particular food specialty. The four species that crush seeds within their bills, for example, should feed on different seeds, those with stouter beaks specializing on harder-to-crush seeds.  FIGURE 8

FIGURE 8

Darwin’s own sketches of Galápagos finches. From Darwin’s Journal of Researches: (1) large ground finch Geospiza magnirostris; (2) medium ground finch Geospiza fortis; (3) small tree finch Camarhynchus parvulus; (4) warbler finch Certhidea olivacea.

©Txtwriter Inc.