Thousands of cancer patients are clamoring this week to be among the 30 or so enrolled in a new and controversial trial designed to seek an answer to this question. One of the most exciting and frustrating things about watching a developing science story like this one is that you can’t flip ahead and read the ending — in the real world of scientific research, you never know how things are going to turn out. The saga of Judah Folkman is very much that kind of story.

Dr. Folkman, a Harvard researcher, is a pioneer in efforts to cure cancer by starving tumors to death. Dr. Folkman’s research follows up on a familiar observation made by many oncologists (cancer specialists), that removal of a primary tumor often lead to more rapid growth of secondary tumors. “Perhaps,” Folkman reasoned, “the primary tumor is producing some substance that inhibits the growth of the other tumors.” Such a substance could possibly be a powerful weapon against cancer.

Folkman set out to see if he could isolate a chemical from primary tumors that inhibited the growth of secondary ones. Two years ago he announced he had found not one, but two. He called them angiostatin and endostatin.

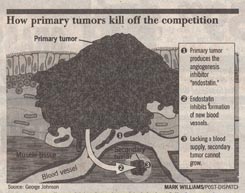

To understand how these two proteins work, put yourself in the place of a tumor. To grow, a tumor must obtain from the body’s blood supply all the food and nutrients it needs to make more cancer cells. To facilitate this necessary grocery shopping, tumors leak out substances into the surrounding tissues that encourage angiogenesis, the formation of small blood vessels. This call for more blood vessels insures an ever-greater flow of blood to the tumor as it grows larger.

When examined, Folkman’s two cancer inhibitors turned out to be angiogenesis inhibitors. Angiostatin and endostatin kill a tumor by cutting off its blood supply. This may sound an unlikely approach to curing cancer, but think about it — the cells of a growing tumor require a plentiful supply of food and nutrients to fuel their production of new cancer cells. Cut this off, and the tumor cells die, literally starving to death.

By producing factors like angiostatin and endostatin, the primary tumor holds back the growth of any competing tumors, allowing the primary tumor to hog the available resources for it’s own use.

In tests in his laboratory, Folkman’s anti-tumor factors caused tumors in mice to regress to microscopic size, a result that electrified researchers all over the world. Other scientists were soon trying to replicate this exciting result. Some succeeded, while others did not. Five major laboratories have made their own endostatin and published their findings of antitumor activity, but other researchers have reported difficulty in repeating the successful tests. National Cancer Institute scientists have replicated Folkman’s results while working in his lab, but failed to get the same results when they went back to their own laboratory.

Why the variability? Purifying finicky natural products in a way that retains their activity can be notoriously difficult. When you don’t know much about the requirements of the factor you are isolating, it can be like grasping smoke.

For example, what if Folkman’s anti-tumor factors turn out to be zinc proteins (that is, they require trace amounts of the metal zinc in order to be active, as many enzymes in the human body do). A little zinc in Folkman’s laboratory water supply — say, the amount in ordinary tap water — might be all that would be required to keep the factors active during the isolation process. Researchers working at The National Cancer Institute, with its ultra-pure zinc-free water, simply might not be supplying the anti-tumor factors the traces of zinc they require.

I don’t think anyone really knows why the isolation works sometimes and not others. That it works at all seems to me the key take-home lesson.

Last month, Folkman announced the isolation of yet a third angiogenesis inhibitor. It is even more potent in reducing blood vessel formation and in shrinking tumors, Folkman claims.

The National Cancer Institute is proceeding with tests of Folkman’s factors in humans, a decision criticized this month by the Wall Street Journal as overhasty, because full-scale animal trials have not been successfully completed.

To me, the NCI decision to proceed directly to human tests seems fully warranted. Human endostatin has been shown to be “completely and utterly safe,” and it clearly has efficacy against mouse tumors. We will learn a lot sooner if this stuff works by proceeding right to human trials, without spending years sorting out the variability of animal trial results. Either we have a powerful new weapon against cancer, or we don’t. Its time to ask — and answer — that question.

©Txtwriter Inc.