One of the great science news stories of the decade is playing out right under our noses, largely unnoticed. Billions of dollars are being spent in laboratories in the United States, Britain, France, Germany, and Japan in a frantic race to see if the secrets hidden within human genes can be revealed to the public before commercial development forever hides them behind a wall of patent secrecy.

Early in this decade the federal government embarked on an ambitious program to produce a full map of the genes in the 46 human chromosomes by the end of 2003. Just as the words on this page are composed of letters arrayed in a certain order, so the DNA of your genes is made of chemical characters arrayed in a particular order. It is the task of the Human Genome Project, directed by Dr. Francis Collins of the NIH, to read each and every gene, writing down all the characters in proper order. Because the human chromosomes contain some 3 billion (that’s 3000 million!) such characters, this task has presented no small challenge, but work has kept on schedule for the planned 2003 completion.

A year ago, in May 1998, a pioneer in DNA sequencing made a startling announcement. Dr. J. Craig Venter, a researcher with his own commercial company (Celera, located in Rockville, Maryland), said in a press conference that his company, with a battery of 300 sequencing machines, will sequence the entire 3 billion letters of human DNA by the end of 2001! Had anyone else made this claim, they might not have been taken seriously, but Venter has proven himself the most successful of all sequencers, sequencing the first bacterial genome in 1995, and more complete genomes than any other researcher.

How could Venter hope to move so fast? Instead of just starting at one end of a chromosome and writing all the DNA characters down in linear order, Venter is focusing on the most interesting bits first. Imagine trying to grasp all the information in a library — Venter is proposing to read all the most popular books first, delaying examination of seldom-checked-out books till later.

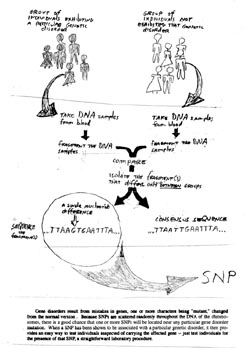

Many (not all) gene sequence researchers feel Venter quite capable of succeeding — so why not let him, and save the taxpayers a billion dollars? Because Venter’s company Celera is a commercial venture, in existence to make money from the knowledge it gains. While Venter plans to release the full “consensus” human genome sequence openly on the internet, and so putting it in the public domain, Celera will patent and keep to itself information on variations in that sequence. Single-character differences, called “single nucleotide polymorphisms,” or SNPs, are spot differences between the version of a gene I have and the one you do, or someone else. The particular importance of SNPs lies in the fact that inherited disorders like cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia are caused by such single-letter typos in genes.

Almost all of the human genome is the same in all of us, and so knowing about it is of little use in combating genetic diseases, but these SNPs are the very stuff of gene disorders. It is the SNPs that Venter proposes to patent. To access the information, pharmaceutical companies and other researchers will have to pay Celera license fees.

Responding to Venter’s challenge, major pharmaceutical companies have in recent months chipped in big bucks to the Human Genome Project to pay for the added sequencing needed to find SNPs. Last week, meeting in closed session, the research labs of the Human Genome Project abruptly changed direction, opting to go for a “blueprint” of the genome first, lest Venter have snared all the interesting SNPS before a more plodding government effort gets to them.

Like a majority of research scientists, I feel that genetic information should remain public — that granting patents for SNPs is the equivalent of letting companies patent basic scientific information. Imagine having to pay a licence fee to examine the periodic table of the elements. A billion dollars is a lot of money to spend trying to beat Venter. By publishing this information first, however, the Human Genome Project will place it forever in the public domain. The secrets of the human genome are worth the price.

©Txtwriter Inc.